The Making of Phacoemulsification

So this is just all kinds of awesome. The amazingly talented Josy Conklin has put together this nifty little video on the making of our recent animation “Phacoemulsification.”

Thanks Josy!

SAMA Fundraising

Just wanted to let everyone know that the Student Association of Medical Illustrators is doing a little fundraiser next Thursday. For those of you in Chicago, feel free to join us at The Drum & Monkey at 1435 W Taylor next Thursday evening.

And since this blog isn’t always read locally, let me direct your attention to the online art auction we will be holding. If you can access this blog, then you can access the auction. Many of us have donated a piece of our work to the cause, and all proceeds will go to benefit SAMA.

“Math Is Not Linear”

Sometimes I let myself diverge here into matters generally scientific or mathematical, rather than outright anatomical because I feel these topics are all related, especially with regard to teaching. Well, Alison Blank has created a wonderful flash project conveying the non-linear nature of math, specifically the matter of learning/ teaching math to students.

If you take the time to explore the piece, you’ll find that you can either click through and be lead from one point to another, or you can simply zoom in and out at your own accord and let your mind wander the topic freely. The medium itself becomes a fantastic exercise in the point itself, that math does not have to be taught linearly. I would say that the same principles hold true with regard to many fields of learning, anatomy and health being no exceptions.

Where there is often frustration diving into such fields, because inevitably those first lessons come without the benefit of understanding related topics, this piece embraces those relationships between ideas and presents a more circular approach to them. It’s really a quite thoughtful, creative, and artistic expression of math and how it can be taught.

CBS at UIC

Ok, so I had to come back in and edit this post a bit today. When I first posted this I had a little laugh at CBS for suggesting UIC’s biomedical visualization program had remote control brain tumor attacking robots. Well it turns out, we may not have robots, but there is in fact an “OR of the Future” project with which the program has involvement. One of the interests of that program is the development of a micro catheter with a specialized operative tip, which utilizes advanced 3D visualization in it’s operation. It actually would be used to get at previously inoperable tumors. So I just thought that was really cool, and worth updating over.

And of course, all of this is regarding the CBS news team that popped by the biomedical visualization department a few days ago. Nice interviews with Scott Barrows, Michaela Calhoun and Leslie (I’m afraid I don’t know her last name). The link to the segment that aired is here.

http://cbs2chicago.com/video/?id=70335@wbbm.dayport.com

I still want the robots though!

Atypical Art by Kasey McMahon

So back in my Los Angeles days I had the pleasure of knowing an artist by the name of Kasey McMahon. It has in fact crossed my mind a few times to post here on her delightfully eerie creation, combining her artistic sensibilities, knowledge of computers, and knowledge of taxidermy, the Compubeaver…

As I recall, it took me hours to work up to touching it back in the time of it’s creation. That was of course *before* my time in gross anatomy.

Well, it has recently come to my attention that she has just launched a new website, and I would like to recommend that everyone check it out.

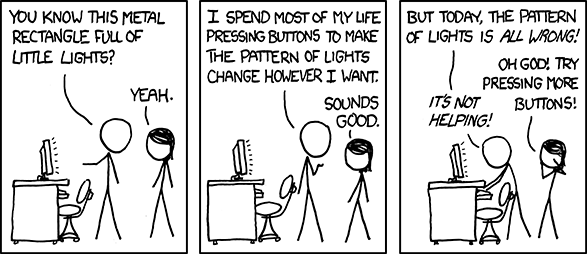

xkcd

So, this pretty well surmises my life of late…

And that is how most medical art is made.

Thank you xkcd for putting it so perfectly.

Phacoemulsification – the video!

It’s official. We have a new medical animation!!!

Now presenting Phacoemulsification!!!

It’s funny, we’ve been working on this all semester long, but only just last night did it hit me that we really have this whole awesome animation.

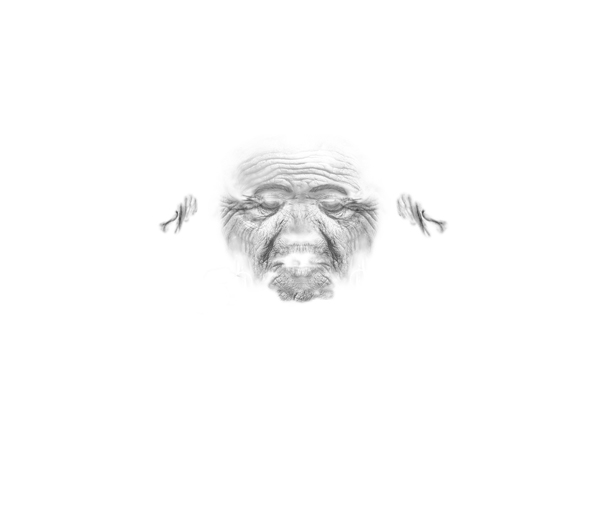

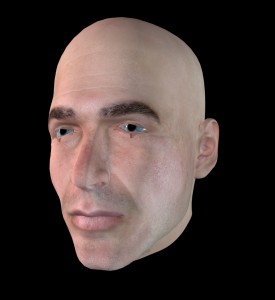

You may remember previous posts about this one, in particular my work with Otis, aka Simon…

Remember Simon?

I originally wrote about him here.

I originally wrote about him here.

Well he’s come a long way what with the wrinkles and the eyebrow fur, and the subsurface scattering. And now he’s the Otis you see in our phacoemulsification video.

Really the whole thing has come such a long way, looking back just two months ago when we were at the animatic stage.

The eyes themselves were done by Josy Conklin, who handled most of the procedural animation along with Matt Cirigliano. Matt also did a good deal of the compositing of those procedural shots, along wtih Eric Small, who did a lot of the special effects, shared most of the instrument modeling with Matt, and who also took on the molecular sequence in Maya.

The only modeling I really did was that of the eye speculum, and just tweaking the pre-fab head our of Poser guy into old age. That was mostly a texturing job though. If anything I hope I didn’t wind up toning all those wrinkles down too far for all the work that went into placing them just so.

The final bump map went something like this…

And the final color map like this…

I had to do a lot of tweaking right around the eyes to avoid distortion with as close as we came in with the camera in 3DsMax. This would be the part where I started using a lot of my house guest’s skin texture in high res photographs to pump up our resolution, while maintaining a blend of aged skin images in the surrounding eye area wherever possible…

There wound up being three main After Effects renders which were then compiled using Premiere. Matt and I are really the most sound effect obsessed, so after compiling our various renders, he and I tackled sound, and also tag teamed on the various titles needed.

All in all, I think the project is a big success. Our instructor suggested this morning that we submit the piece to this summer’s AMI annual meeting in Portland. I think we will.

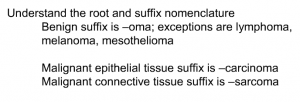

just another little rant about educational wording

So I’m reviewing some Pathophysiology lectures before taking an online test this morning, and I just have to say that there is one slide that bugs me so much! The lecturer starts with the explanation that the suffix -oma refers to benign tissue growths, mentions one example of when this works, and then gives THREE exceptions!

The lecture then goes on to explain that malignant tissue growth often takes the suffix -carcinoma or -sarcoma. And at no point is it so much as acknowleged that both -carcinoma and -sarcoma end in -oma!

Now I know that we are talking about individual suffixes across various tumor growths here, and that technically -carcinoma would be the entire suffix, not just -oma, but why on earth would you not start with the specific terms and then move on to say that the benign tissue growths don’t take on the the entirety of these suffixes, but do still end in -oma.

The way this is set up is needlessly confusing!

To be fair, most of these slides are actually handled pretty well. But man, I see stuff like that and it just bugs me!

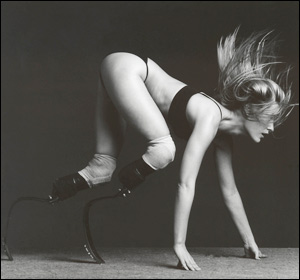

The Open Prosthetics Project

A friend of mine sent me a couple of links last night…

The first, was written for Gizmodo by Aimee Mullins. “Is Choosing a Prosthesis So Different than Picking a Pair of Glasses?”

The second was a response article by Kevin Connolly posted at Boingboing. “Open Source Prosthetics”

Both speak to the expense of prosthetic limbs, and the difficulty of obtaining a quality prosthesis, let alone two, especially through standard insurance coverages. Aimee on the one hand, has taken the route of obtaining and trying out every new prosthetic technology available. In her own words…

“To be frank, since my teenage years, I have pursued each and every opportunity to be a guinea pig, trading the use of my body as a testing ground for new technologies for the privilege of using them. Not one pair of my legs is covered by insurance; not one pair of my legs is considered ‘medically necessary.’ ”

Kevin on the other hand, speaks of growing up with an interest in finding simple affordable solutions to his physical condition. In his own words…

“I remember always feeling a mix of awkwardness and obligation when I slid into the big, wobbly, pair of legs. The only element that kept me in prosthetics was the reminder from doctors, family, and therapists of the time and money they took to create.

At every possible opportunity, I would abandon the legs in favor of running on my hands — or later in life, using a skateboard. I found that the practicality and affordability of these two options allowed for more financial and logistic freedom for getting around the everyday world.”

I suppose the two articles represent a sense of designer work versus open source. So while Aimee brings attention to her Ossur legs and her Dorset legs, both fantastic designs in prosthetic limbs, Kevin brings attention to The Open Prosthetics Project, a more DIY approach to dealing with amputation or limb deficiency.

Personally, I hadn’t ever heard of this before, and I can’t help but feel a little excited about it. I’ve seen a lot of really good things come out of open source and DIY designs and I’m really interested to see what comes out of this.

**Just a quick edit here – I just learned that Aimee Mullins was interviewed on The Colbert Report, not even two weeks after this was written here. You can see the interview here…

http://www.colbertnation.com/the-colbert-report-videos/271372/april-15-2010/aimee-mullins

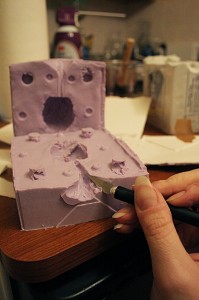

New Tricks For Me in Mold Making

Recently I had the opportunity to learn about a different kind of mold making. In my modeling classes at school, we have worked in plaster, and constructed 3-part molds for prosthetic ears. This time I got a glimpse into some different tactics and materials for mold making with sculptor, Ian Coulter.

The first thing was finding something to copy. After a lot of sculpting and striving for that perfect thing to replicate, we decided to take something old and flawed, and really push the limits of what we could get. So we picked an old sculpture I had done of Norman Mailer, my first likeness, which minutes after baking I managed to slam a lid onto and crack open.

The next step was making a box to house the mold. For this we started with a milk carton.

I am told that some people go to a lot of trouble to build wooden boxes for this purpose, but the wax paper used in your basic carton seems to do the trick just fine. So we got to cutting this one open.

Once cut open into a foldable box, the sculpture gets placed onto a soft round ball of molding clay. We called this ball the base.

We then went ahead and drew a line around the point to which we intended to build this half of the mold. And then we made long snakes out of the modeling clay and began wrapping outward to fill that half of the mold.

We used smaller snakes right around the sculpture, and larger snakes as we reached the edges of the box. Using the snaked shape helps later when you have to get all this stuff back off again.

The clay will then be smoothed out to prevent the rubber from seeping down into the cracks when it gets poured later.

A toothpick makes a good tool for cleaning up the area right around the sculpture itself.

A heat gun makes a good tool for melting the fingerprints out of the clay and getting things extra smooth.

Keeping the surface of the clay smooth is important because this will become the surface between the two rubber halves of the mold later on, and any divits or scratches could potentially become mechanical adhesives and cause problems with opening and closing the mold later.

Next it was time to think about where we would be pouring in to. We chose the base of the head because it had less detail than the face or hair and therefore could be sanded off if need be later.

We cut a straw and placed it to create this space.

Using the cap of my X-acto knife we set up four primary keys around the piece.

We used a sharpie to set up some lesser keys as well. The important part about this part is ensuring that these indentures go straight up and down. Once again, you want to avoid mechanical barriers to opening your mold back up again. But you do want both sides of the mold to lock into alignment and resist side to side slipping.

The next step is getting that box back together and sealed up with tape.

Now you’re ready to mix up some rubber!

In my case it was Aero Marine silicone RTV rubber, with purple catalyst.

As is typical with silicones, you mix them at a 10-1 ratio. It makes a big goopy mess, and you can take your time getting it into the box because this stuff takes a good long while to dry.

Once your rubber is mixed, you can get the best results by painting some directly on to the sculpture. This allows you to push the material into all the cracks and crevices and avoid air bubbles getting caught in your detail. Use a brush you don’t mind loosing for this task.

Then you can just pour the rest over the top and let it settle on down. When I did this I made it a point to rattle the box a little, pick it up and drop it a few times, to move any trapped air upward. At school we have an actual vibrating plate to do this with plaster. This rubber actually did a pretty good job moving air upward on it’s own, what with the slow drying time. This half of the mold took about a day and a half to dry. The other half I sped up by adding more catalyst and as a result did catch more air bubbles in that half (though still none anywhere that really mattered).

We left the rubber to set for the next couple days, braced between a bottle of oil and the package of modeling clay for extra support. With the slow dry, you could actually blow air bubbles away off the surface as they rose to the surface.

I wound up waiting longer than I needed to because rather than put fingerprints into the mold itself I was testing the bowl and spatula where the rubber had been mixed to know when it was cured. Well I hit a surprise when something was going on with the spatula that inhibited the curing of the rubber.

I have no idea what caused this. Ian tells me that he has used a similar spatula time and time again for this process. My only guess is that some chemical be it from a food or cleaning agent affected the rubber of the spatula over the years and turned out to be an inhibitor. I never was able to fully get the stuff off of it.

The mold itself set just beautifully though.

Once open, I just flipped it over and started peeling away the modeling clay. It is important when you do this not to move the original sculpture. I found it helpful to remember the base we had started with when I got to this part. That little circle marks the most clay against the sculpture.

From here you just want to trim up the edges of your mold and clean off any excess modeling clay that has stuck to your original sculpture.

Once cleaned up, it’s time to paint some release over the rubber. I went ahead and coated the sculpture too on account of all the detail in the hair.

Unfortunately the product I used for a release turned out to be a poor choice. I have since been advised that the important detail to look for is that you use something acrylic. In my case I used a polymer varnish that I commonly use with my acrylic paints, but that is not acrylic itself. Next time I intend to use my Speedball matte medium acrylic polymer instead.

Once the release is set, it’s time to tape the box back up and pour the other side. Again, you want to start by painting the sculpture directly first.

In my case, I tried placing a little piece of Super Sculpey against the wall to help with opening the mold later. Given the troubles I had with the release, this did wind up helping a little, but really that’s a more useful trick in plaster than it is in rubber. Once this side has set, you have yourself a mold!

It’s a really strong mold too. When the release I painted failed, I knocked this thing all over the place trying to get it open. I literally jumped up and down on top of it at one point to loosen the seam. It was literally an all day process ripping this thing open.

And then finally, I had an open mold!

So then I checked the channel left by the straw, ensuring clear passage for the resin to pour, and cut a funnel shape into the surface side of the mold.

If you intend to use the mold for a lot of copies, it’s best to use some form of barrier around the sculpture’s impression to prevent the mold from drying out. I didn’t use anything for the first couple pours, but then later I experimented with baby powder. I’m told that WD40 is great for this as well.

You then want to close the mold and band it together.

The resin I used was a two part mix, mixed at a one to one ratio. From what I understand, this is typical of resins.

Before you start mixing up your resin, it’s best to have some idea how much you’re going to need. To accomplish this, I poured some water in a cup and marked a line at it’s surface level. Then I placed the sculpture into the water and marked the point to which the water level rose. Doing this with an actual measuring cup would of course be a more accurate accounting for the amount of resin needed, but I didn’t have one handy, so the visual was at least helpful in making an estimate.

The resin once mixed, gets poured into the funnel shape, and down the channel to fill the impression inside. The resin starts setting up in about ten minutes time, so you have to do this quickly. My first pour ran into trouble, as I kept getting stuck on the air inside by pouring down the only channel. This made the pour too slow, and before I could get it all in, the resin began to heat and harden and I was out of luck.

So before pouring the next one, I cut in an extra air escape channel. I’m told that with practice it gets easier to keep the poured resin stream thin enough to run down the edges and not require an extra air channel. That makes sense, but this was easier.

It worked like a charm too. The next pours went much better.

The only problem I continued to have was the one piece of the mold that rose slightly above the pour point. Try as I might, I couldn’t quite get a solid pool of resin in there.

When I got a chance to ask about it later I was advised to cut the pour channel to bring resin in from the top. I haven’t tried that yet, but it sounds reasonable. The next mold I make, I’ll be sure to channel the pour in to the highest point in the sculpture to avoid similar difficulty.

All in all, I was really impressed with the accuracy and detail of these materials. The resiliency of the rubber was really impressive as well. To be able to go from literally jumping on the mold to getting such impeccably detailed copies was really amazing.

I am really looking forward to utilizing the rest of this stuff for my next project – pocket study skulls!

If you would like to see more images from my time experimenting with this stuff, I’ve posted them all over at http://snapshotgenius.com/gallery/firstrubbermold